From Food Security to Nutrition Security: Bridging the Gap for a Healthier World

Photo: K. Trautmann via Flickr

“Fighting global food insecurity means more than feeding the world – it also means nourishing the world. Calories alone are insufficient to increase individuals’ well-being, fuel economic growth and build resilient, prosperous communities.”

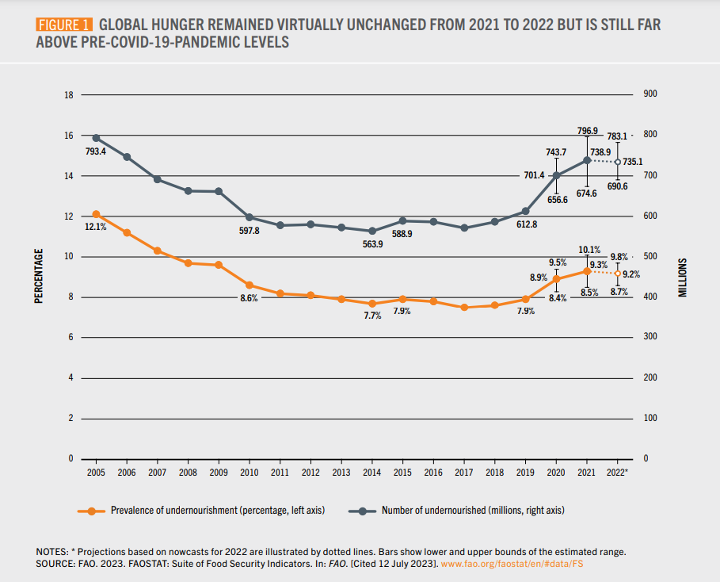

After more than 3 years of worst-case scenario hunger headlines, this year’s plateau in global food insecurity was, relatively, a breath of fresh air. Global hunger remained relatively unchanged this year, and we saw the gender gap in food insecurity, which got worse during the pandemic, decrease by 37%.

But despite these positive-seeming signs, we are not yet out of the woods. Global food insecurity remains far worse than it was in 2019, with 122 million more people facing hunger in 2022 than in 2019. Ongoing conflict, as well as climate and economic shocks, threaten to tip the scales and send food insecurity numbers surging again. In this crisis, it is easy to view the quality of calories as less important than the quantity, but there are millions of vulnerable people who cannot sustain themselves on calories alone. Experts estimate that over half of preschool-aged children and two-thirds of non-pregnant women of reproductive age worldwide have micronutrient deficiencies. Even if we fed every hungry person today, millions of women and children would still be malnourished, jeopardizing their wellbeing and limiting countries’ overall potential and growth. As we focus on the monumental task of addressing these sky-high rates of global hunger, we must ensure achieving nutrition security is a fundamental component of our food security strategy.

Nutrition security means making sure people not only have enough to eat, but that they have sufficient nutrients to ensure they are not malnourished. It means moving beyond solutions focused merely on providing hungry people with starchy staples that may be able to sustain life but are insufficient to meet their nutritional needs. It means ensuring people have access to diverse diets that include fruits, vegetables, legumes, and animal-sourced foods. When healthy diets are unavailable, it means providing stop-gap nutrition interventions, like specialized food supplements and fortified foods, and screening and treating severely malnourished children promptly with ready-to-use therapeutic foods (RUTF).

Nutrition is often sidelined as a secondary component of food security efforts, but for vulnerable groups, it is often the difference between life and death or a barrier to a child developing to their full potential. The most vulnerable of these groups are children in the 1000-day window between pregnancy and a child’s second birthday for whom even a short bout of malnutrition can cause lifelong physical and cognitive consequences leading them to perform less well in school and earn less as adults. We also know that in times of food insecurity, women often bear the brunt of the hunger burdens for their families, eating last and least to help food stretch further. We must ensure these women get the nutrition care they need, both for their own sakes and because malnourished mothers often give birth to malnourished babies, perpetuating an inter-generational cycle of malnutrition.

To build true food security, we must draw from models that build resilience across vulnerable communities. One such model is the U.S. Department of State’s Vision for Adapted Crops and Soils (VACS) which focuses on developing climate-resilient varieties of nutritious, indigenous crops with the potential to diversify diets and reduce rates of malnutrition. Similarly, initiatives that strengthen and embed nutrition interventions into national health systems build community resilience to food shocks by ensuring nutrition care continues even when food availability diminishes.

In the coming years, the world will face numerous threats to global food security, the most serious of which is likely the growing threat climate change poses to the quantity and quality of food that is available. Increasingly frequent climate shocks will make crops harder to grow and livestock harder to raise which will ultimately decrease food supply and incomes for agricultural workers. The food that does grow will be less nutritionally dense. In the face of these challenges, we will need to take concrete steps to shore up global food security. Clear plans to address malnutrition along with hunger will be key to any successful strategy.